The Amalgamation Of Nigeria Was A Fraud

by

Richard Akinjide, QC, SAN

July 9, 2000

Lagos - I Was in the first cabinet that was overthrown by the military

in this country. I entered parliament in December 12, 1959. And I

remained in Parliament until January 15, 1966 when the Government was

overthrown. I was the Federal Minister of Education in that cabinet.

I woke up in the morning in my official house in Ikoyi to discover

that my telephone was not working. I had never experienced coup before

nor did I know that it was a coup, thinking it was just a telephone

fault; until a colleague of mine in the cabinet Chief Abiodun Akerele,

came in and told me there had been a military coup. So I had the fortune

or the misfortune of being a victim of the first coup ever in this

country.

Many people may not know that I spent 18 months in detention in

prisons across the country. I've spent the time in Kirikiri prison,

Ilesha prison, Ibadan prison and the Abeokuta prison Two of us who were

in Balewa's government emerged when the military handed over to

civilians in 1979 as part of the civilian Government. In Balewa's

government, Alhaji Shehu Shagari was the Minister of Works while I was

the Minister of Education. When the Military handed over to us after

about 14 years, Shagari emerged as the President, while I became the

Attorney - General and Minister of Justice. Again, Shagari's government

was overthrown just a few months after I left the cabinet. Of course, we

suspected it was coming.

A lot of things that happened between that period and now would never

see the light of the day. When you are in government, you know a lot of

things; you see a lot of things. A lot of things you know or did or saw

will die with you. This is the practice the whole world. People have

asked me to write my memoirs, I just laugh because there are certain

things I can never reveal. When I was in Tafawa Balewa's Cabinet, all

Cabinet ministers had access to written intelligence

report every month. That was the practice at that time. But when Shagari

came in, for reasons, which I cannot explain, that practice was no

longer followed. But by virtue of my duties as the Attorney - General

and as a member of the National Security Council, I continued to have

access to some sensitive matters.

Nigeria is a very complex country. Our problems did not start

yesterday. It started about 1884. Lord Lugard came here about 1894 and

many people did not know that Major Lugard was not originally employed

by the British Government. He was employed by companies. He was first

employed by East Indian Company, by the Royal East African Company and

then by the Royal Niger Company. It was from the Royal Niger Company

that he transferred to the British government. Unless you know

this background, you will not know the root causes of our problems. The

interest of the Europeans in Africa and indeed Nigeria was economic and

it's still economic. They have no permanent friends and no permanent

interests. Neither their interests nor their friends are permanent.

Nigeria was created as British sphere of interests for business. In

1898, Lugard formed the West African Frontier Force initially with 2,000

soldiers and that was the beginning of our problems.

Anybody who wants to know the root cause of all the coups and our

present problems, and who does not know the evolution Nigeria would just

be looking at the matter superficially. Our problems started from that

time. And Lugard was what they called at that time imperialist. A number

of British soldiers, businessmen, politicians were very patriotic. But I

must warn you; they were operating in the interest of their country.

Lugard became a Lord.

Nigerians, too, should operate in the interest of their country. When Lugard

formed the West African Frontier Force with 2,000 troops, about 90 percent

of them were from the North mainly from the Middle belt. And his dispatches

to London between that time and January 1914 are extremely interesting.

Lugard came here for a purpose and that purpose was British interest. Between

1898 and 1914, he sent a number of dispatches to London which led to the

Amalgamation of 1914.

The Order - in - Council was drawn up in November 1913 signed and

came into force in January 1914. In those dispatches, Lugard said a

number of things, which are at the root causes of yesterday and today's

problems.

The British needed the Railway from the North to the Coast in the

interest of British business. Amalgamation of the South (not of the

people) became of crucial importance to British business interest. He

said the North and the South should be amalgamated. Southern Nigeria

came into existence on January 1900 ... At the Centenary of the fall of

Benin, I wrote a piece in a number of papers but before I published the

piece, I sent a copy to the Oba of Benin. So when Benin was

conquered in 1896, it made the creation of the Southern Nigerian

protectorate possible on January 1, 1900.

If you remember, Sokoto was not conquered until 1903. So, there was

no question of Nigeria at that time. After the conquest of Sokoto, they

were able to create the northern Nigerian protectorate. Lugard went full

blast and created what was to be known as the protectorate of Northern

Nigeria. What is critical and important are the reasons Lugard gave in

his dispatches. They are as follows: He said the North is poor and they

have no resources to run the protectorate of the

North. That they have no access to the sea; that the South has resources

and have educated people.

The first Yoruba lawyer was called to the Bar in 1861. Therefore,

because it was not the policy of the British Government to bring the

taxpayers money to run the protectorate, it was in the interest of the

British business and the British taxpayer that there should be

Amalgamation. But what the British amalgamated was the Administration of

the North and South and not the people of the North and the South, that

is one of the root causes of the problems of Nigeria and the

Nigerians.

When the amalgamation took effect, the British government sealed off

the South from the North. And between 1914 andl960, that's a period of

46 years, the British allowed minimum contact between the North and

South because it was not in the British interest that the North be

allowed to be polluted by the educated South. That was the basis on

which we got our independence in 1960 when I was in the parliament. I

entered Parliament on December 12, 1959. When the North formed a

political party, the northern leaders called it Northern Peoples

Congress (NPC). They didn't call it Nigeria Peoples Congress. That was

in accordance with the dictum and policies of Lugard. When Aminu Kano

formed his own party, it was called Northern Elements Progressive Union

(NEPU) not Nigerian Progressive Union.

It was only Awolowo and Zik who were mistaken that there was anything

called Nigeria. Infact, the so-cared Nigeria created in 1914 was a

complete fraud. It was created not in the interest of Nigeria or

Nigerians but in the interest of the British. And what were the

structures created? The structures created were as follows: Northern

Nigeria was to represent England; Western Nigeria like Wales; Eastern

Nigeria was to be like Scotland. In the British structure, England has

permanent majority in the House of Commons. There was no way Wales can

ever dominate England, neither can Scotland dominate Britain. But they

are very shrewd. They would allow a Scottish man to become Prime

Minister. They would allow a Welsh man to become Prime Minister in

London but the fact remains that the actual power rested in England.

That was what Lugard created in Nigeria, a permanent majority for the

North. The population figure of the North is also a fraud. Infact, a

British Colonial Civil Servant who was involved in the fraud was trying

to expose it but he was never allowed to publish it. The analysis is as

follows: If you look at the map of West Africa, starting from Mauritania

to Cameroun and take a population of each country as you move from the

coast to the Savannah, the population decreases.

Or conversely, as you come from the Desert to the Coast, right from

Mauritania to the Cameroun, the population increases. The only exception

throughout that zone is Nigeria. Nigeria is the only zone whereby you

go from coast to the North, the population increases and you come from

the North to the Coast, the population decreases. Well, geographers,

anthropologists and population experts, draw your conclusions, Someone

has told me the last population census was done by

computer, what a nonsense.

A computer is as good as its programmer. A computer will produce what you

ask it to produce. I have read this book from cover to cover. This is a

fantastic book. I want us to find a way to ensure that as many Nigerians

read this book. It is a raw material for future authors. There is one thing

which is missing in the book and that is the first broadcast of General

Ibrahim Babangida when he assumed power in 1985. That broadcast is very

crucial to the economic problems we have today. ... Talking on the first

coup, when Balewa got missing, we knew Okotie- Eboh had been died, we knew

Akintola had been killed. We, the members of the Balewa cabinet started

meeting. But how can you have a cabinet meeting without the Prime Minister

acting or Prime Minister presiding. So, unanimously, we nominated acting

Prime Minister amongst us. Then we continued holding our meetings. Then

we got a message that we should all assemble at the Cabinet office. All

the Ministers were requested by the G.O.C. of the Nigerian Army, General

Ironsi to assemble.

What was amazing at that time was that Ironsi was going all over Lagos

unarmed. We assembled there. Having nominated ZANA Diphcharima as our acting

Prime Minister in the absence of the Prime Minister, whose whereabout we

didn't know, we approached the acting President, Nwafor Orizu to swear

him in because he cannot legitimately act as the Prime Minister except

he is sworn- in. Nwafor Orizu refused. He said he needed to contact Zik

who was then in West Indies.

Under the law, that is, the Interpretation Act, as acting President,

Nwazor Orizu had all the powers of the President. The GOC said he wanted

to see all the cabinet ministers. And so we assembled at the cabinet

office. Well, I have read in many books saying that we handed over to

the military. We did not hand-over. Ironsi told us that "you either hand

over as gentlemen or you hand-over by force". These were his words. Is

that voluntary hand-over? So we did not

hand-over. We wanted an Acting Prime Minister to be in place but Ironsi

forced us, and I use the word force advisedly, to handover to him. He

was controlling the soldiers.

The acting President, Nwafor Orizu, who did not cooperate with us,

cooperated with the GOC. Dr. Orizu and the GOC prepared speeches which

Nwafor Orizu broadcast handing over the government of the country to the

army. I here state again categorically as a member of that cabinet that

we did not hand-over voluntarily. It was a coup. This is a very good

book, which everybody must read. It is raw material for future authors.

Anybody, who wants to know some of the causes of our

problems, military instability should read this book. I even recommend

this book to all universities and secondary schools, so that they can

know how we get to where we are now. What this book shows is that if

anybody stages a coup and if people don't accept it, it would not

succeed. What puzzles me is how the author got all these materials. He

must have connections in high places to be able to get a lot of these

materials.

These materials should not be in the archives, they should be in the

public domain so that we know the causes of our problems. I pray that

all Nigerians should rise up and say no if anybody seizes a radio

station and says "fellow countrymen". I hope that this book will find

its way into all university libraries throughout this country, to all

secondary school library and abroad. I appeal to the media to give this

book a comprehensive and desired review.

The more I open the book, the more I see something to talk about.

This book is going to represent one of those chapters in the tragedy of

Nigeria. This book is just like horror film because the instability

which was started in I966 ... because many of the coups are what I'll

call commercial coups. If anything at all, we have to learn a great

lesson from this book and also learn a lesson on what happened, who

failed or succeed in their coups. When it succeeds. They call it

glorious revolution. But when it fails, it is called treason. It is my

honour and privilege to present this great and historic book. One of the

things I like about the book is the language of the author. He's

someone who speaks Englishman's English. He writes Queen's English. Very

lucid, very flowing.

|

|

Country

Profile |

| Federal Capital: Abuja |

Business Hours: |

| Area: 923,768,64 Sq. Km |

Banks: 8 a.m. - 3 p.m. Monday only |

| Population: 110 Million |

8 a.m. - 1.30 p.m. Tues. - Fri. |

| Principal Rivers: Niger and Benue |

|

| Independence Day: October 1 |

Federal Government Offices: |

| Remembrance Day: January 15 |

7.30 a.m. - 3.30 p.m. Mon. - Fri. |

| Currency: Naira

= 100 Kobo |

|

| Time: GMT + 1 EST + 6 |

Commercial Offices: |

| Climate: Humid Sub-Tropical |

8.00 a.m. - 5.00 p.m. Mon. - Fri. |

| Weights and Measures: Metric |

|

| Legal and Tax: British Oriented |

International Airports: |

| VAT: 5% (Introduced Jan. 1994) |

Lagos: Murtal Muhammed Airport |

| Dailing Codes: - in code (Outside)234 |

Abuja: Nnamdi Azikiwe Intl.Airport |

| Dailing Code: - out code 009 |

Port Harcourt: Port Harcourt Intl. Airport |

| |

Kano: Kano International Airport |

|

Summary:

Summary: |

1862 (January 1): Lagos

Island annexed as a colony of Britain

Mr. H.S Freeman became Governor of Lagos Colony (Jan.

22)

1893: Oil

Rivers Protectorate renamed Niger Coast Protectorate

with Calabar as capital.

1890's: British reporter Flora Shaw, who later married Lord Frederick Lugard,

suggests that the country be named "Nigeria" after the Niger

River.

1897: The British overthrew Oba Ovonramwen of Benin,

one of the last independent West African kings.

1900: The Niger Coast Protectorate, merged with the colony and protectorate

of Lagos, was renamed the Protectorate of Southern Nigeria

Lord Fredrick Lugard

|

1914: The northern and southern protectorates were amalgamated to form

Nigeria. Colonial officer Frederick Lugard was governor-general.

1929 (October): Women in the eastern commercial city of Aba held a rowdy

but effective and victorious protest against high taxes and low prices

of Nigerian exports.

1951: The British decided to grant Nigeria internal self-rule, following

an agitation led by the NCNC, Dr Azikiwe’s political party.

1954: The position of Governor was created in the three regions (North,

West and East) on the adoption of federalism.

1958: Nigerian Armed Forces transferred to Federal control. The Nigerian

Navy was born.

1959: The new Nigerian currency, the Pound, was introduced

1959: Northern Peoples Congress (NPC) and Niger Delta Congress (NDC) formed

an alliance to contest parliamentary elections.

1960 (October 1): Independence. Dr.

Nnamdi Azikiwe became Nigeria’s first indigenous

Governor General.

1960-1966: First Republic of Nigeria under a British parliamentary system.

Abubakar Tafawa Balewa was elected Prime Minister.

1960: Nigeria's joined with Liberia and Togo in the "Monrovia Group",

seeking some form of a confederation of African states.

1961 (February 11 and 12): After a plebiscite, the Northern Cameroon, which

before then was administered separately within Nigeria, voted to join Nigeria.

But Southern Cameroon became part of francophone Cameroon.

1961 (June 1): Northern Cameroon became Sardauna Province of Nigeria, the

thirteenth province of Northern Nigeria as the country’s map assumed a

new shape.

1961 (October 1): Southern Cameroon ceased to be a part of Nigeria.

1962:Following a split in the leadership of the AG that led to a crisis

in the Western Region, a state of emergency was declared in the region,

and the federal government invoked its emergency powers to administer the

region directly. Consequently the AG was toppled as regional power. Awolowo,

its leader, and other AG leaders, were convicted of treasonable felony.

Awolowo's former deputy and premier of the Western Region formed a new

party--the Nigerian National Democratic Party (NNDP)--that took over the

government. Meanwhile, the federal coalition government acted on the agitation

of minority non-Yoruba groups for a separate state to be excised from the

Western Region

1963: Nigeria shed the bulk of its political affinity with the British

colonial power to become a Republic. Nnamdi Azikiwe became the first President.

Obafemi Awolowo leader of the Action Group (AG) became leader of the opposition.

The regional premiers were Ahmadu Bello (Northern Region, NPC), Samuel

Akintola (Western Region, AG), Michael Okpara (Eastern Region, NCNC). Dennis

Osadebey (NCNC) became premier of the Midwestern Region just created out

of the old Western region.

1964: Prime Minister Balewa’s Northern Peoples Congress (NPC) aligned with

a faction of the Action Group (AG) led by Chief Ladoke Akintola, the Nigerian

National Democratic Party (NNDP), to form the Nigerian National Alliance

(NNA) in readiness for the elections. At the same time, the main Action

Group led by Chief Obafemi Awolowo formed an alliance with the United Middle-Belt

Congress (UMBC) and Alhaji Aminu Kano's Northern Elements Progressive Union

(NEPU) and Borno Youth Movement to form the United Progressive Grand Alliance

(UPGA).

1965 (November): Violence erupted in the western region, and criticism

of the political ruling class created unease in the new republic.

1966 (January 15): Junior officers of the Nigerian army, mostly majors

overthrew the government in a coup d’etat. The officers, most of whom were

Igbo, assassinated Balewa in Lagos, Akintola in Ibadan, and Bello in Kaduna,

as well as some senior northern officers. The coup leaders pledged to establish

a strong and efficient government committed to a progressive program and

eventually to new elections. They vowed to stop the post-electoral violence

and stamp out corruption that they said was rife in the civilian administration.

General Johnson T. Aguiyi-Ironsi, the most senior military officer, and

incidentally an easterner (Igbo), who stepped in to restore order, became

the head of state.

1966 (May 29): Massive rioting started in the major towns of Northern Nigeria

and attack the Igbos and other easterners to avenge the death of many senior

northerners in the coup.

1966 (July 29): A group of Northern officers and men stormed the Western

Region’s governor’s residence in Ibadan where General Aguiyi Ironsi was

staying with his host, Lt. Col Adekunle Fajuyi. Both the head of state

and governor are killed.

1966 (August 1): Lt. Col Yakubu Gowon a fairly junior officer from the

north became the new head of state.

1967 (January 4): Nigeria's military leaders travelled to Aburi in Ghana

to find a solution to problems facing the country and to avert an imminent

military clash between the north and the east.

1967 (May 30): Lt Col Ojukwu, governor of the east, declared his region

the Republic of Biafra.

1967 (July 6): First shots were fired heralding a 30-month war between

the Federal government and the rebel Republic of Biafra.

1970 (January 15): The civil war ended and reconstruction and rehabilitation

begin.

1971 (April 2): Nigeria switches with amazing smoothness from driving on

the left hand side (like Britain) to the left, like all its neighbouring

countries.

1973 (May): Gowon establishes the National Youth Service Corps Scheme and

introduces compulsory one-year service for all university graduates, to

promote integration and peace after the war.

1974: General Gowon said he could not keep his earlier promise to return

power to a democratically elected government in 1976. He announced an indefinite

postponement of a programme of transition to civil rule.

1975 (July): Gowon was overthrown in a coup, on the anniversary of his

ninth year in office. Brigadier (later General) Murtala Mohammed, the new

head of state promised a 1979 restoration of democracy.

1976: The federal government adhering to the recommendations of a panel

earlier set up to advise it, approves the creation of a new Federal Capital

Territory, Abuja, away from Lagos.

1976 (February 13): Murtala Mohammed was killed in the traffic on his way

to work. But the coup executed by an easy-going physical education corps

Lt colonel, and heralded by a quixotic announcement on the radio, was botched.

1976 (February 14): General Mohammed is succeeded by General Olusegun Obasanjo

who pledged to pursue his predecessor’s transition programme.

1976 (September 2): The Universal Primary Education Scheme (UPE) was introduced,

making education free and compulsory in the country.

1977: Nigeria hosted FESTAC the festival of arts and culture drawing black

talent and civilization from around the world.

1979: Nigeria got a new constitution.

1979 (October 1): General Obasanjo handed over to Alhaji Shehu Shagari

as first elected executive President and the first politician to govern

Nigeria since 1966. Five parties had competed for the presidency, and Shagari

of the National Party of Nigeria (NPN) was declared the winner. The other

parties were: Unity Party of Nigeria (UPN), National People’s Party (UPN),

Great Nigeria People’s Party (GNPP), People’s Redemption Party (PRP)

1983: The conduct of the general elections was criticised by opposing parties

and the media. Violent erupted in some parts of the west.

1983(September): Shagari was re-elected president of Nigeria in August-September

1983.

1983(December 31): Following a coup d’etat, the military returned to power.

Major-General Muhammadu Buhari was named head of state.

1985 (August 27): Following accusations of callousness and overzealousness,

Buhari was overthrown in a palace coup. The army chief, General Ibrahim

Babangida took over power.

1986: The seat of government was officially moved from Lagos to Abuja

1993 (June 12): After several postponements by the military administration,

presidential elections were held. Businessman and newspaper publisher Moshood

Abiola of the SDP took unexpected lead in early returns.

1993 (June 23): Babangida on national television offered his reasons for

annulling the results of the Presidential election. At least 100 people

were killed in riots in the southwest, Abiola's home area.

1993 (August 26): Under severe opposition and pressure, Babangida resigned

as military president and appointed an interim government headed by Chief

Ernest A. Shonekan.

1993 (October): A ragtag group of young people under the name of Movement

for the Advancement of Democracy (MAD) hijacked a Nigerian airliner

to neighbouring Niger in order to protest official corruption. Nigerian

troops stormed liberated the plane at the N’djamena airport, Republic of

Niger.

1993 (November 17): General Sani Abacha, defence minister in the interim

government and most senior officer, seized power from Shonekan, abolishes

the constitution.

1994: Abiola, who had escaped abroad after the annulment, returned and

proclaimed himself president. He was arrested and charged with treason.

1995 (July): Former head of state, Obasanjo was sentenced to 25 years in

prison by a secret military tribunal for alleged participation in an attempt

(widely believed to have been fictional) to overthrow the government.

1996 (May): Nnamdi Azikiwe, Nigeria's first president, died.

1998 (June 8): General Abacha died suddenly and mysteriously. The official

cause of death: heart attack. Nigerians swarmed the streets rejoicing.

1998 (June 9): Gen. Abdulsalaam Abubakar was named Nigeria's eighth military

ruler. He promised to restore civilian rule promptly.

1998: A month after General Abacha's death the United

Nations General-Secretary Kofi Annan arrived in Nigeria

to conclude deals for the release of Chief Abiola.

1998 (July 7): Abiola died in detention of a heart disease, a week after

Annan’s visit, before he could be released in a general amnesty for political

prisoners. Rioting in Lagos led to over 60 deaths.

1998 (July 20): Abubakar promised to relinquish power on May 29, 1999.

1999 (February 15): Former military ruler Obasanjo won the presidential

nomination of the Peoples Democratic Party (PDP).

1999 (May): A new Constitution was adopted. It was based on the 1979 Constitution.

1999 (May 29): Former Military Head of State, Olusegun Obasanjo, was sworn

in as Nigeria's democratically elected civilian President.

|

|

|

|

Lugard And Colonial Nigeria – Towards An Identity?

This original article, titled “Lugard And Colonial Nigeria – Towards An

Identity?” was written by the great historian, Michael Crowder – History

Today, February 1986, Vol. 36, pp 23 – 29. I am again merely reproducing

this fine piece that throws more light on the feud and rivalry between

our colonial administrators and which seem to have been passed down to

us, and is the causative of most of the ethnic distrust and problems that

still exist in Nigeria today. I am sure many Nigerians, especially historians,

have read this article, but then, most of us who are not students of history

might not have come across it. Certainly, I had not, until quite recently,

and it was a fascinating read and knowledge. It is a long article, but

I hope you will take your time to read through and enjoy this part of our

history....Akintokunbo Adejumo

Here we go: (“More

like sovereign heads of state than servants of the same British Crown” –

the rivalry and ‘diplomacy’ of imperial proconsuls hampered the

creation of Nigeria between 1900 and 1914)

Lugard’s arrival at Calabar on a tour of the Central and Eastern Provinces, Dec. 1912 DIPLOMACY IS NOT AN ACTIVITY usually associated with colonies or colonial

officials. By definition colonies were not sovereign states and where relations

with other countries were concerned, these were conducted for them by their

imperial governments. Likewise, the colonial official did not ‘represent’

his country in his colony, even when he bore a diplomatic title like that

of ‘Resident’ in Northern Nigeria, but rather exercised power on its behalf

over people who had lost their sovereignty. Given this, a special problem arose as to how to

conduct relations between colonies occupied by the same metropolitan

power that were territorially contiguous but administered as separate

entities. To take Africa as an example, Britain after the First World

war had nine contiguous colonies in East, Central and Southern Africa,

while France had seventeen in Northern, Western and Equatorial Africa.

How were conflicts of interest between neighbouring countries

administered by the same colonial power to be solved, or projects of

mutual economic interest to be advanced? The French partially solved

this problem by placing their West African colonies under a

Governor-General in Dakar, and their Equatorial African colonies under a

Governor-General in Brazzaville, thus reducing the potential areas of

inter-colonial conflict to those between the French Equatorial

Federation and the French West African Federation, and between the

latter and the French North African possessions of Morocco and Algeria,

with which it had common borders. The British, who delegated more power

to their proconsuls in Africa than did the French, expected them to

settle any disputes that might arise between them on the spot, keeping

the overworked and understaffed Colonial Office informed of results, but

only in the last resort referring to it for arbitration. The

three contiguous British territories of the Niger – the Lagos Colony and

Protectorate, and the Protectorates of Northern and Southern Nigeria –

provide a fascinating case study of the way in which these contiguous

British administrations conducted relations with each other very much as

would friendly (and sometimes not so friendly) sovereign states with

particular concerns, boundaries and ways of life to defend. Before the

Protectorate of Northern Nigeria was formally proclaimed in 1900, it was

declared British policy to amalgamate it with its southern neighbours.

The fact it took fourteen years to amalgamate them, was in large part

due to often bitter ‘diplomatic’ wrangles between their respective

officials, and the way these officials perceived their colonies as

‘countries’ with special interests which it was their business to

protect. Sir Frederick Lugard, as High Commissioner of the Protectorate

of Northern Nigeria, highlighted the anomalies of this situation when he

wrote to Sir William MacGregor, Governor of the Lagos Colony and

Protectorate, over the boundary between the two British territories in

March, 1902: "I venture to remind Your Excellency that though,

in my opinion, it matters little where the exact frontier is placed,

since both Protectorates are British, since before long it is your hope

and mine that they will become still more closely connected, and since I

have the good fortune to have succeeded in working in co-operation and

harmony with Your Excellency, still I have an obligation no less than

that which you so strongly feel yourself to safeguard the traditional

and just rights of the chiefs within my administration". The

three British colonial possessions of the Niger that were amalgamated

between 1906 and 1914 each had a different origin which helped determine

the specific character they quickly developed under their British

administrators. The oldest of the three was the Lagos Colony and

Protectorate, dating back to 1861 when the British occupied the

island-port of Lagos to put an end to its involvement in the slave trade

and to protect British commercial and evangelical interests in the

hinterland. The subsequent occupation of its hinterland was accomplished

in the last decade of the nineteenth century, mainly peacefully through

treaties with the kings of the Yoruba states who made up this largely

ethnically homogenous, though politically fragmented, territory. A

substantial group of Yoruba-speaking people were, however, included in

the Northern Protectorate since in the early nineteenth century they had

incorporated into Ilorin, one of the constituent emirates of the great

Sokoto Caliphate, whose lands comprised nearly two-thirds of that

Protectorate. A small group of Yoruba were to be found in the extreme

western areas of the Southern Nigerian Protectorate. Lagos island itself

and a small part of the mainland had the status of a Crown Colony with

its own Executive and Legislative Council established at the time of the

British occupation in 1861, while the larger hinterland was a British

Protectorate.

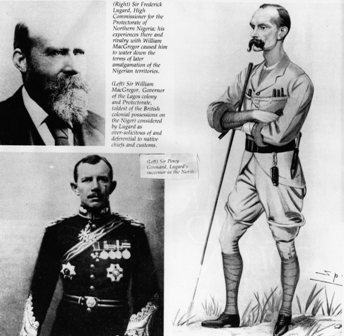

Top Left: Sir William MacGregor, Governor of the Lagos Colony and Protectorate

Right: Sir Frederick Lugard, High Commissioner for the Protectorate of Northern Nigeria

Bottom Left: Sir Percy Girouard, Lugard’s successor in the North. To

the east of the Lagos Colony and Protectorate lay the Protectorate of

Southern Nigeria, much of which in 1900 still had to be conquered or, in

British colonial parlance, ‘pacified’. This Protectorate, formed from

the old Niger Coast Protectorate and part of the lands of the Royal

Niger Company, whose status as a Charter Company with the right to

administer territory on behalf of the Crown had been withdrawn the year

before, comprised a multitude of different ethnic groups. Its origins

went back to the mid-nineteenth century when British consular officials

began to exercise authority over certain coastal states in an attempt to

suppress the slave trade and protect the interests of British palm-oil

merchants. It was ruled from Old Calabar in the far south-eastern corner

of the territory by Sir Ralph Moor. The Protectorate of

Northern Nigeria, proclaimed on January 1st, 1900, when the British flag

was hoisted at Lokoja at the confluence of the Benue and the Niger, was

formed from lands claimed, and to a much lesser extent administered, by

the Royal Niger Company along the Niger and Benue river valleys and to

the north of them. Sir Frederick Lugard, who had earlier secured some of

these territories for the Company, now became the Protectorate’s

founding High Commissioner. As Margery Perham, his biographer wrote: "A

colonial governor can seldom have been appointed to a territory so much

of which had never even been viewed by himself or any other European". It

may seem curious that so soon after their conquest, and given the

arbitrary nature of their boundaries and the heterogeneity of the

peoples and polities enclosed within them, these British-created

colonies could even be thought of in terms of countries. Yet, within a

short space of time, their respective colonial administrations had

imposed on them a separate, albeit British-derived identity, in terms of

differing legal systems, administrative organisation and patterns of

economic development. The administrators of these three territories saw

them as having the attributes of countries and, if they were to be

amalgamated, as all were agreed they eventually should, this should be

done on terms that were in no way disadvantageous to their individual

interests. The actual decision to amalgamate the British

territories on the Niger had been taken as early as 1898 by a six member

Niger Committee. The Colonial Office was represented by the Earl of

Selbourne and Mr Reginald Antrobus; the Foreign Office, which was still

responsible for the Niger Coast Protectorate, by Sir Clement Hill; while

the Niger Territories themselves were represented by Sir Henry

McCallum, Governor of Lagos, Sir Ralph Moor, Consul-General of the Niger

Coast Protectorate, and Sir George Goldie, head of the Royal Niger

Company, part of whose territories were to make up the future

Protectorate of Northern Nigeria. All were agreed that the long

term goal should be the amalgamation of the three territories. For the

present this was impractical because of lack of communications and the

problem of the climate which dictated the appointment of younger men as

senior administrators and would make it difficult to find a man with

sufficient seniority to oversee all three territories. At this early

stage, differences of opinion began to emerge between the British

officials on the spot as to what form the organisation should take. Moor

favoured the immediate amalgamation of Lagos and the Niger Coast

Protectorate under one administration as the Maritime Province.

McCallum, who had initially favoured the idea, subsequently formed the

‘decided opinion’ that it would be impossible under the present

conditions for one man to rule effectively over the whole of the

suggested Maritime Province. Antrobus agreed with McCallum that it would

be difficult to put the two southern administrations under one

government, ‘although if communications were easier there would no doubt

be advantages in doing so’. Chamberlain, as Secretary of State

for Colonies, accepted that for the time being there should be three

territories, so in 1900, with the declaration of the British

protectorate of Northern Nigeria, the renaming of the Niger Coast

Protectorate as the Protectorate of Southern Nigeria and the retention

of the Lagos Colony and Protectorate as a separate administrative

entity, there were established three British administrations on the

Niger whose long-term goal was amalgamation. But as the Nigerian

historian and administrator, Isaac N Okonjo, so shrewdly observed: "Not

for the last time were British political officers to identify

themselves too closely with the interests of the region of Nigeria in

which they served and which they had grown to love at the expense of the

wider interest of the country as a whole". The principle source

of friction between the three territories on the Niger was the

demarcation of their boundaries with each other. Indeed sometimes

negotiations over these were more difficult of settlement than those

over their frontiers with their French and German neighbours. Certainly

the latter sets of boundaries were more speedily determined. Indeed some

stretches of boundary between the northern and southern protectorates

had not been fixed by the time of their amalgamation in 1914. The

principal source of friction lay on the boundary between Northern

Nigeria on the one hand and the Lagos and Southern Protectorate on the

other. The acrimony that developed between MacGregor of Lagos and Lugard

of the North over the towns of Kishi and Saki underlines the fact that

these British officials acted as though they were representing separate

states, not colonies belonging to the same colonial power. Kishi and

Saki were Yoruba towns with which Lugard, when an official of the Royal

Niger Company, had made treaties. Now, as High Commissioner of Northern

Nigeria, which had inherited the northern territories of the RNC, he

considered these two towns properly belonged to him. Furthermore, he

considered these relatively populous towns essential as bases for the

opening-up of the less populous non-Yoruba country to their north, known

as Borgu, which was clearly part of his domain. MacGregor argued that

both Saki and Kishi traditionally paid allegiance to the Yoruba ruler of

Oyo, which clearly lay in his domain, and therefore, they should come

under his jurisdiction. As early as April 1900, with Lugard’s

agreement, Macgregor set off on journeys into parts of Yorubaland

claimed by the North. Not only did MacGregor pass on to the Colonial

Office complaints made by Yoruba towns he claimed for Lagos about

‘forcible and harmful interference by officers of Northern Nigeria, of

whom our boundary natives stand in unreasonable and unreasoning dread’,

but he alleged that these border towns had also a ‘great dread of being

transferred to Northern Nigeria’. MacGregor also wrote that he

considered that he had already ‘shown that it is impossible for Lagos to

cede Kishi’ (The author’s italics). Lugard, who considered

MacGregor over-solicitous of, and deferential to, his ‘native chiefs’.

Was particularly annoyed at the charges laid against his officers.

Indeed he wrote to MacGregor that apart from not feeling it necessary to

represent to the Secretary of state complaints against or adverse

reports upon Lagos officials: ‘….I deprecate allowing natives to

practice their traditional policy of playing off the officials of one

Administration against that of the other’. Even so, Lugard has

MacGregor’s charges investigated and one of the border officials, Pierce

M Dwyer, Assistant Resident in Ilorin, assured him ‘that during my

period of service in Illorin [sic] I have been most careful to refrain

from any act that might be considered by the Lagos Government as

interference’. The boundary disputes between Moor and Lugard were no less acrimonious.

The basic differences between the two were summed up by Captain Woodruffe,

one of the Southern Boundary Commissioners, who held that they: "Arose from the fact that

from the Northern Nigerian point of view, geographical considerations

were of little or no importance….further….the Political Officer,

Northern Nigeria, stated that he did not see what race, Native Custom

and tradition had to do with the question as he, personally, did not

consider the natives had any feelings of sentiment or cling to customs

and laws they and the people before them were used to, and further, in

his opinion that if any natives were ordered by one Government or the

other to go either North of South they would do so". The

Southern Boundary Commissioner, by contrast, considered that ‘natives

were very much in the habit of maintaining their old allegiance, however

slight’. Although Moor and Lugard signed an agreement with

regard to their boundary west of the Niger, they were unable to settle

that east of the Niger. They did, however, come to an understanding as

to what was for the time-being workable, and agreed joint patrols along

their undefined borders because the ‘natives’ in the area were not yet

‘pacified’. But the divisions between them were too deep. In the event

Lugard appealed to the Secretary of State for a ruling, talking about

the question of transfer of lands in terms of ‘cession’. Meanwhile he

assured Moor that he had not been ‘activated by hunger for land’. Matters

were easier on the Lagos-Southern Nigerian Protectorate frontier. But

even though disputes concerned matters of much less moment, such as the

position of a marker point in a river, they were sometimes referred

home. As Bull minuted to Antrobus on Moor’s despatch about the markers: "It is merely a question of words, and it is a little surprising that

a man of Sir R Moor’s capacity should have referred home on such a point,

when he has been told that Mr Chamberlain is prepared to agree to anything

he may settle with OAG (Officer Administering the Government) Lagos in

this matter. But these internal boundary questions, though trivial, have

a knack of bringing out the most businesslike characteristics of all three

administrators of Nigeria". While the objective of amalgamating the three Nigerian

territories had been established by the Niger Committee from the outset,

no time limit had been set for its achievement. The Committee did,

however, recommend that the three territories form a Customs Union

pending amalgamation, and Lugard, before assuming duties in the North,

had proposed in 1899 that he would adopt the same ‘customs, regulations

and management’ as Southern Nigeria and Lagos ‘in so far as they are

applicable to an inland territory’. But once out in Northern Nigeria,

Lugard established a customs policy of his own. Tolls were imposed on

goods entering the Northern Protectorate by road from the Southern

Protectorate, though goods shipped along the rivers Niger and Benue went

free. The African merchants of Lagos were particularly resentful of

these tolls and of their status as ‘aliens’ in Northern Nigeria. Indeed

by the terms of the Land Proclamation of 1900, no-one who was not a

native of the Northern Protectorate could directly or indirectly acquire

interest in and rights over land within the Protectorate from a

‘native’ without the consent, in writing, of the High Commissioner.

But

this did not mean that Lugard was against amalgamation, indeed, for

Lugard, ruling over the newest and largest of the three territories,

amalgamation was, curiously, the most urgent. In the first place,

Northern Nigeria was landlocked and could therefore; earn no direct

revenue from duties on imports or exports. Instead the Southern Nigeria

Protectorate made an annual grant of £34,000 in respect of the duties it

was estimated it would be able to raise if it had its own port; but the

Southern administration protested that effectively only £12,000 would

in reality have been raised on the volume of external trade emanating

from the North. In the second place much of the North was still outside

administrative control and Lugard required an Imperial Grant-in-Aide to

complete its conquest and establish his administration. This subjected

him to a degree of metropolitan control that the two Southern

Protectorates did not suffer. If he could amalgamate with a southern

territory with sufficient a surplus in its revenue to cover his deficit,

he would be relieved of irksome control by an Imperial Treasury that

held that all colonial dependencies should pay their own way. MacGregor

and Moor were equally anxious to amalgamate with the North so the

railway that they both planned to extend from their seaboard to the

interior could thus penetrate and open up their natural hinterlands

without hindrance.

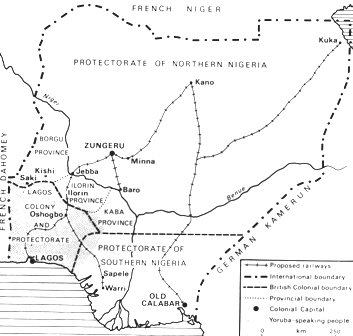

Map of Nigeria before amalgamation showing the three Protectorates and Provinces

(Akintokunbo Adejumo: Please note the Cameroon border and relate to Bakassi Province today) As

far as the Colonial Office was concerned, the main stumbling block on

the road to amalgamation was ‘the personalities of the administrators of

the three provinces’. Nevertheless in 1903 a major step towards

amalgamation of the two coastal protectorates was taken when Sir Ralph

Moor was replaced by Sir Walter Egerton, who was appointed

simultaneously Governor of the Lagos Colony and Protectorate and of the

Protectorate of Southern Nigeria. Even so it took some three years to

bring the two territories together because Egerton seemed to take the

sides of both parties to the proposed union and wrote in 1905 to

Lyttleton at the Colonial Office that the future amalgamation of

Northern Nigeria and Southern Nigeria would be: "Much simpler

than that between Lagos and Southern Nigeria, for the different systems

of government, laws, and methods adopted in the latter two

administrations forbid a complete union for some time to come". Thus

he proposed to the Colonial Office a form of amalgamation of Lagos and

Southern Nigeria that approximated to a confederation with separate

institutions. The two Southern protectorates were finally and,

at Colonial Office insistence, fully amalgamated on February 26th, 1906,

to become the Colony and Protectorate of Southern Nigeria with its

capital at Lagos. Meanwhile disputes between the Northern and Southern

Protectorates continued unabated particularly in matters of railway

policy and boundaries. Indeed these two areas of potential conflict

became inextricably bound up as the Lagos line began to cross the

frontier into Northern Nigeria. Lugard’s successor, Sir Percy

Girouard, was first and foremost a railway engineer and administrator,

with experience in the Sudan, Egypt and South Africa. His appointment

was a temporary one and had been made with a view to bringing some

rationale into plans to join up the Lagos line with the Northern line. By

the time he took up his appointment Girouard found that the two

Nigerias had rival railway projects. From the port of Lagos the Southern

Nigerian administration was building a 3’ 6” gauge line northwards to

the Niger at Jebba in Northern territory. Meanwhile Lugard had been

planning a 2’ 6” line from Kano to Baro on the Niger which would enable

him to ship produce without passing through Southern Nigerian territory

since under the terms of the Berlin Convention of 1885 the Niger was an

international waterway. The Southern Nigerian Government did not

want its railway to be subject to Northern control even when it passed

through the latter’s territory. Egerton therefore urged that the area of

Northern Nigeria southwest of the Niger be transferred to his

administration. But Girouard would have none of this, being as

protective of Northern interests as his predecessor (Lugard). Almost as

if to add insult to injury, the Colonial Office ruled that the rich

Southern Protectorate should provide the deficit-ridden Northern

Protectorate with the funds to finance its Baro line, since in any case

the two protectorates were destined shortly to be amalgamated. But he

did gain two major concessions: there was to be no hold-up in the

construction of his own line to meet up with the Northern line near

Zungeru, the northern capital, and more important still, the Northern

line should be of similar gauge to his own so there would be no

difficulty in transferring good from one line to the other. Otherwise

had the Northern line remained at 2’ 6” gauge, it would have favoured

onward carriage of northern goods from Zungeru to Baro rather than Lagos

even at the time of the year when only shallow draft steamers could

operate on the Niger. But Egerton was to lose his other argument that at

least he should have control of the land on either side of his railway

as it passed through Northern territory. Right up to the eve of

amalgamation of the Northern and Southern Protectorates wrangles between

their respective administrations over control of the northern sector of

the Lagos line continued with the North accusing the South of refusing

to book goods bound for Jebba and shipment down the Niger and the South

accusing the North of giving preferential treatment to those who chose

to export goods via Baro and the Niger rather than through Lagos.

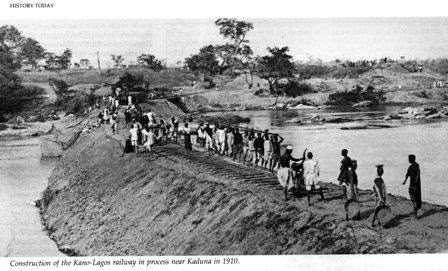

Construction of the Kano-Lagos railway in progress near Kaduna in 1910 Apart

from the major territorial claim made by Egerton to the Kabba and

Ilorin provinces, disputes over the demarcation of the existing boundary

between the North and the South continued. However, they never reached

the acrimony that had existed between Lugard and MacGregor, and then his

successor Egerton, which culminated in Lugard writing to the Under

Secretary of State for Colonies when he was on leave in Abinger before

taking up his post in Hong Kong: If Sir Walter Egerton intends

forthwith to carry out his own view [with regard to the frontier] and

will send his own officer to lay out a line in accordance with them [it

will compel] the Government of Northern Nigeria to oppose such a course

of action by force or refer the matter to the Secretary of State for a

decision. The most bitter dispute was along the boundary

eastward from the Niger to the border with German Kamerun. Once again we

see that the administrations of the two Protectorates had come to

regard themselves as representing separate countries with distinct

identities. One sector of the boundary divided the Tiv people, one of

Nigeria’s largest ‘minority’ groups. Girouard urged that the whole of

Tiv country should be brought under his administration. To this Egerton

replied that, since they were a ‘pagan’ people, ‘very similar to other

pagan races in Southern Nigeria’, the reverse should be the case.

‘Southern Nigeria Officers have infinitely greater experience in the

treatment of the Pagan peoples, in their habits and methods of

government than Northern Nigeria officials …’ In urging the Colonial

Office to transfer Tiv country to Southern Nigeria he added a number of

other claims, notably Ilorin: "Sir Percy Girouard and myself,

however, hold very opposite views regarding the development of Northern

Nigeria. Sir Percy is content to develop the country without assistance

from outside and demurs to the entry of Southern Nigeria natives. I, on

the other hand, think that equilibrium between revenue and expenditure

can be best effected by encouraging intercourse between the North and

South….." At this time, the Tiv were still resisting the

imposition of British rule. Since they were divided between the two

administrations both were engaged in ‘punitive expeditions’ against

them. Here Egerton stipulated that he did not wish Southern Nigeria

troops to be involved in operations in Northern Tivland. Tiredly, Bull

in the Colonial Office minuted to a colleague: ‘As one expected, he

(Egerton) is very jealous of the boundary between Southern and Northern

Nigeria.’ Particularly galling to Egerton and his Southern

Nigerian subjects were the taxes that continued to be imposed on them

when trading in the Northern Protectorate. They resented being treated

as though they were foreigners there. Their alien status in that

territory was re-emphasised in 1910 by the Land and Native Rights

Proclamation which gave the Northern administration control over

immigration from the south by with-holding the grant of a certificate of

occupancy or by attaching restrictive conditions to a grant, or by

threatening to revoke it. In the Colonial Office the principle

of eventual amalgamation had never been in question: the real problem

was to find the man capable of undertaking it. The matter had achieved

an urgency in recent years because of what Okonjo has called, somewhat

melodramatically, the collapse of the Southern Nigerian Administration

in the face of activities of lawyers. Egerton put the position as seen

by his administration succinctly in a letter to Lord Crewe, the Colonial

Secretary. Although the jurisdiction of the Supreme Court extended

throughout the Southern Protectorate he considered that its most

backward parts were: "Quite unfitted for so highly organised

jurisdiction, little inconvenience and liaison resulted from its

introduction until the advent within the last few years of native

barristers from Sierra Leone and the Gold Coast who have adopted the

habit of sending their agents through the country touting for cases and

inducing towns, which before the advent of civil control, would have

fought over matters, to pay them extortionate fees to bring suits in the

Supreme Court…..Naked savages are now, through the agency of lawyers,

bringing cases before the Supreme Court." These lawyers, Okonjo

convincingly argues, succeeded in hamstringing the administration to

such an extent that in places it came to a standstill. The Northern

Nigerian Government had taken powers from the beginning to exclude

barristers from the Provincial Courts of the Protectorate. Thus, when

Lugard, coming to the end of his term as Governor of Hong Kong in 1911,

indicated that he would be willing to undertake the task of amalgamating

the two Nigerias, he seemed the ideal choice. Matured by years, and

with direct experience of administering Northern Nigeria, which he had

done so much to build and which ran so smoothly compared with the

disarray in which its southern counterpart found itself, he appeared to

be as likely as anyone to be able to join the two parts into an

effective whole. The consequences for Nigeria’s long-term

political development of the formula Lugard chose need not concern us

here except in two respects. The first is that not surprisingly Lugard’s

amalgamation largely involved imposing on Southern Nigeria the

administrative and judicial systems of the North. The second was that

the amalgamation was only a partial one. Whereas the Colonial Office has

overruled Egerton’s scheme for partial amalgamation of the two southern

territories in 1906, they allowed Lugard’s scheme to go ahead. He

received a number of suggestions as to how the huge Northern

Protectorate might be broken up to give the constituent units of the new

Nigeria greater balance. But Lugard had created Northern Nigeria and he

was clearly not prepared to see his ‘country’ lose its identity. The

farthest he was prepared to go was to suggest a return to the pre-1906

situation by re-establishing the former Lagos Colony and Protectorate as

a separate constituent unit of amalgamated Nigeria. As it was,

Lugard’s amalgamation was more like a loose federation of two countries,

each of which retained its own administration, headed by a

Lieutenant-Governor with his own Secretariat, budget and departments.

Only Posts and Telegraphs, Survey, Audit, Judiciary and Military were

centralised under Lugard as Governor-General. Southerners continued to

be treated as aliens in the north. The consequences of this partial

amalgamation were to haunt Nigeria for the next fifty years and many

would argue that the Nigerian civil war had its roots in the form of

amalgamation Lugard imposed on the country. * * * The

amalgamation of the three British territories on the Niger, agreed in

principle in 1898, took nearly sixteen years to achieve because the

administrators of these territories often behaved more like sovereign

heads of state than servants of the same British Crown. They and their

subordinate officials conducted relations with each other as though they

were dealing with foreign governments rather than neighbouring British

administrations whose frontiers had been largely arbitrarily delimited

and were soon to be joined together as one unit. From a rational

point of view these frontiers should have been of as little

consequences as those between British counties. As it was the most

disputes between the three administrators on the Niger were over

borders, the very stuff of diplomacy. Rational economic co-operation

between them was bedevilled not by irredentism on the part of the

inhabitants who had been unwillingly enclosed by the colonial frontiers,

but of their colonial overloads. British officials identified fiercely

with the colonies they had been sent out to govern and serve in, as

fiercely as they had with their public schools or universities. Thus

Sylvia Leith-Ross, sailing out to Nigeria for the first time in 1907

with her husband who was the Chief Transport Officer in the Northern

Protectorate, was surprised to find that the Purser would never dream of

placing Northern and Southern officials at the same table. The

‘Northerners’ looked down on the ‘Southerners’ who they considered

flabby and who began drinking at 6pm, whereas they did not start until

6.30pm. What is so remarkable about these ‘national identities’

is that they took root so quickly, feeding of course on existing ethnic

and religious differences, and were used as we have seen to defend one

British territory against encroachment – territorial or economic – by

the other, even though they were soon to be joined together. By giving

so much autonomy to their proconsuls, the British Colonial Office made

amalgamation most difficult of realisation and brought about a situation

in which in their conduct of relations with each other, they were bound

to act more like heads of state than civil servants of the same

government department – which of course, they were.

The doctor starting his morning rounds by railroad, Ilorin, October 1912 FOR FURTHER READING: This

article is based primarily on the relevant papers of the Colonial

Office held in the Public Records Office at Kew. Margery Perham, Lugard:

The Years of Authority 1899-1945 (Collins, 1960); Isaac M Okonjo,

Administration in Nigeria 1900-1950 (New York, 1974); T K Tamuno, The

Evolution of the Nigerian State: The Southern Phase, 1898-1914 (Longman,

1972); Robert Heussler, The British in Northern Nigeria (Oxford

University Press, 1968); A.H.M. Kirk-Greene ed., Lugard and the

Amalgamation of Nigeria: a documentary record, London, 1968. This article is reproduced from Lugard And Colonial Nigeria – Towards An Identity?

By Michael Crowder – History Today, February 1986, Vol. 36, pp 23 – 29 Michael Crowder was born in London on 9 June 1934 and educated at Mill

Hill School. During his national service he was seconded to the Nigeria

Regiment (1953-1954). He gained a 1st class honours degree in Politics,

Philosophy and Economics (PPE) at Hertford College, Oxford University in

1957. He returned to Lagos to become first Editor of Nigeria Magazine,

1959-1962, and then Secretary at the Institute of African Studies at the

University of Ibadan. In 1964-1965 he was Visiting Lecturer in African

History at the University of California, Berkeley, and in 1965-1967 was

Director of the Institute of African Studies at Fourah Bay College, University

of Sierra Leone. From 1968 to 1978 he was based in

Nigeria again, first as Research Professor and Director of the Institute

of African Studies at the University of Ife, then from 1971 as

Professor of History at the Ahmadu Bello University (also becoming

Director of its Centre for Nigerian Cultural Studies, 1972-1975) and

finally as Research Professor in History at the Centre for Cultural

Studies at the University of Lagos, 1975-1978. He returned to London in

1979 to become editor of the British magazine History Today and is

credited with making a significant contribution to the survival and then

success of the magazine as it now is. He remained a Consultant Editor

up to his death.

He returned to the academic world as Visiting

Fellow at the Centre for International Studies at the LSE, 1981-82, and

then as Professor of History at the University of Botswana, 1982-85.

From 1985 until his death he was Joint Editor of the Journal of African

History. In 1986 he became Visiting Professor in Black Studies at

Amherst College, Massachusetts, USA and Honorary Professorial Fellow and

General Editor of the British Documents on the End of Empire Project at

the Institute of Commonwealth Studies (ICS). His death on 14 August

1988 was marked by obituaries in the four major daily London newspapers

and in many academic journals. For a bibliography

[incomplete] of Crowder's works, see J.F. Ade Ajayi & John D.Y. Peel

(eds.), People and Empires in African History: Essays in Memory of

Michael Crowder (London, Longman 1992) pp.x-xiv. His major publications

include: The Story of Nigeria (1962, 4ed. 1977); West Africa under

Colonial Rule (London, Hutchinson 1968); jt.ed., The History of West

Africa (London, Longman 2 vols 1971-74, 2 ed. 1985-87); West African

Resistance (London, Hutchinson 1971); Nigeria: an Introduction to its

History (London, Longman 1979); ed. Cambridge History of Africa, vol.

VIII (CUP 1984);'I want to be taught how to govern, not to be taught how

to be governed': Tshekedi Khama and the opposition to the British

administration in the Bechuanaland Protectorate, 1926-30 (University of

Malawi 1984); The Flogging of Phinehas McIntosh: a tale of colonial

folly and injustice - Bechuanaland, 1933 (New Haven, Yale University

Press 1988); with N. Parsons, eds., Monarch of All I Survey:

Bechuanaland Diaries, 1929-37 by Sir Charles Rey (Gaborone and New York

1988).

|